How prisoners participated in the daily life of Americans

The smaller branch camps in North Carolina offered the possibility for farmers to approach the camp guards and hire a group of POWs for six to ten weeks for the same pay as civilian workers. The U.S. government would then assist with transportation to the farms and back to the camps at night. Prisoners would even receive the payment they could exchange for vouchers [1].

Interestingly enough, POWs were not only used as farm helpers. The University of Chapel Hill and Duke University hired 110 prisoners from Camp Butner in 1945 as waiters on campus. Not much information can be gathered from available archival sources of these Universities about their interaction with Americans, but it is fascinating how German POWs were occupied in various branches of American life [2].

Transatlantic friendship

Only by the end of the war did the American public find out about the presence of German POWs in the United States. In comparison to how Germans treated American POWs abroad and operated concentration camps, many American citizens regarded U.S. treatment of German POWs treatment as “coddling” and too soft. It took an immense amount of effort by the U.S. government to calm the public down [3]. German prisoners left North Carolina gradually and by 1946, the final group of POWs left American soil.

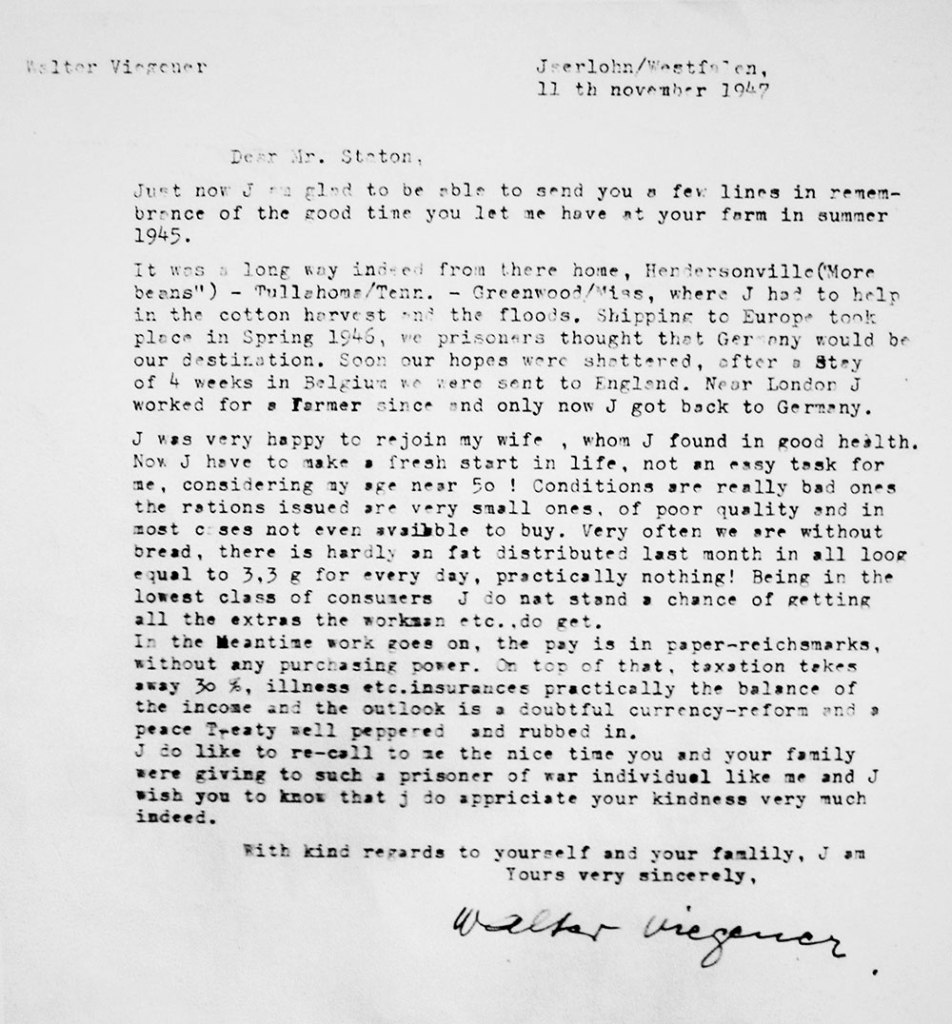

Despite the rise in a public outcry by the end of the war, Americans and Germans found an unlikely friendship. After prisoners left, communities that were in contact with these prisoners often spoke kindly of them. A man, who was only a young child during the 1940s, recalls being invited for a little bit to eat when delivering newspapers to the military base where the POWs resided. Others remembered the Germans as hardworking, efficient, and friendly [4]. On the other hand, Germans would tell their families about the friendly Americans they encountered and how good they were treated upon their return to their homeland. On top of that, as many German soldiers did not immediately return to Germany, but were instead sent to British or French prisoner of war camps to rebuild cities and factories, POWs who had formally been held in America, now longed for the U.S. Many former POWs have returned to North Carolina since the end of the war and many tell their stories of their time as a prisoner in a tone of gratitude [5].

My grandfather was one of them. My father told me how Americans took my grandfather and his fellow prisoners for a ride and how he was working a sweat from doing woodwork in the beating heat in North Carolina. Moreover, he always told me how Americans are very nice people and always treated him with respect. I think he planted a seed for my curiosity towards the US and influenced my decision to study American Studies when he told me these stories. He and other former POWs were part of an influential group that bonded with American residents and founded a deep friendship even in the face of the cruel realities of the war.

Bibliography

[1] Billinger, Robert D. “Behind the Wire: German Prisoners of War at Camp Sutton, 1944-1946.” The North Carolina Historical Review 61, no. 4 (1984): 482.

[4] Billinger, Robert D. “Behind the Wire: German Prisoners of War at Camp Sutton, 1944-1946.” The North Carolina Historical Review 61, no. 4 (1984): 486.